Michie Gleason: A Small Boat on a Becalmed Sea

Interruption is stress; it hinders creativity. For a writer in the midst of deep thought, it’s a shock to the system. You have to go back and start over. Ideas get lost.

One of the great gifts of my SSB artist residency in Tuscany was being able to get up every morning and jot down first thoughts while drinking coffee in the garden, knowing there would not be any interruptions.

My subject, the controversial painter known as Balthus, is famous for his infatuation with pubescent and pre-pubescent girls, but also for his mysterious, dreamlike imagery, which seems clearly inspired by early encounters in Tuscany with the work of Piero della Francesca.

Balthus was born in Paris to Polish parents forced to leave France, like everyone else of German descent, at the start of World War I. His father abandoned the family; his mother Baladine took him and his younger brother to Switzerland. She began a love affair with Rainer Maria Rilke, who seemed equally taken with her and her young sons.

Balthus showed Rilke a series of woodcuts he had made, depicting the story of a cat found, loved, and finally lost. Rilke—the most famous German-language poet of the time—recognized the 13-year-old boy’s talent and wrote the introduction and arranged for the publication of the drawings.

Baladine’s affair with Rilke was tempestuous. When he would leave her, so he could write in solitude, Baladine leaned on Balthus for emotional support. From the age of 12 to 13, he was his mother’s confidante, and the famous poet who had replaced his father was his mentor. A complex situation—especially for a sensitive boy at a young age.

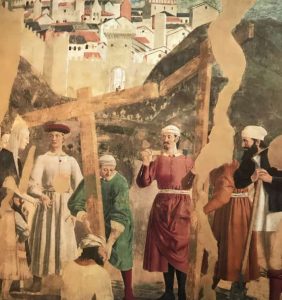

Balthus returned to Paris to study painting. He discovered Piero della Francesca, and embarked on a pilgrimage to Italy to visit some of his great works. With sketching tools on his back, Balthus hiked to Sansepolcro, where Piero was born and lived most of his life. He visited Monterchi, where he saw the Madonna del Parto; and in Arezzo went to the Basilica di San Francesco, which houses The Legend of the True Cross frescoes. When I walked into the basilica for the first time and saw the frescoes, I too was astonished. The first word that comes to mind is “modern.” After so many ornate masterpieces of the Renaissance, suddenly you encounter simple, clean composition; elegant geometry; a restrained palette. Piero’s characters are big-boned and straightforward. They seem modeled on rural people he must have grown up with. Their faces lack the detail that generally conveys complex emotion, but are infused with a painted light that conveys transcendence. That, I think, is their mystery. In that basilica I could imagine the young Balthus, enthralled by his first great inspiration.

My first encounter with Balthus’ work was in New York, during my college years in rural New England. I especially remember The Mountain. The painting seemed populated by people my age in the midst of grand nature, very stoned. I especially remember Thérèse Dreaming. As an art student influenced by Germaine Greer, I was angered and often bored by the male gaze.

The painting did not offend me. I thought of girls in our culture, raised from day one to be self-conscious, especially about their bodies. What I remembered about Thérèse was how relaxed she seemed, how she was caught up in her daydream, utterly free of self-consciousness. She wasn’t some David Hamilton fantasy; she was a real girl, a new image.

Now it’s the era of #MeToo. Balthus is way out of fashion. A couple of years ago, two art students started an online petition asking the Metropolitan Museum of Art to reimagine how they present Thérèse Dreaming. Within an hour, I think, they had over 10,000 signatures. The museum was not persuaded, but the next time I stopped by, the painting had been taken down, replaced by Balthus’ quite ordinary portrait of his art dealer, Pierre Matisse.

The questions I asked myself during my long walks through the Tuscan countryside considered the ways one artist is inspired by another…how one artist adapts an inherited technique to their own subject matter. I thought about Balthus, caught in an Oedipal triangle, perhaps trying to recreate in his art the innocence he felt he had lost. I thought about the ways people are defined by contradictions they are unable to reconcile.

Did he use women, the way male artists often do, as a substitute for his own vulnerability? After his first marriage, in some relationships with his models, he certainly abused his power…but in what ways? It’s almost natural to abuse power—once one has it—so I want to characterize this very precisely.

I realized that what I was looking for in Tuscany was nuance. We are all beset by flaws. Part of being human and living with others involves balancing acceptance of those flaws with the need for reckoning. This is not always easy: it’s a partisan world. We’re pushed into good/bad…one dimensional assessments of character. Many writers know specificity is what makes characters memorable. There are many strands to specificity—it’s a complex notion. We’re looking for secrets our characters don’t even know they have.

In my previous post, I spoke of my walks in the Val d’Orcia, surrounded by rolling green hills, experiencing the sensation a local man described as “bobbing up and down in a small boat on a perfectly becalmed sea.” With Piero’s images in my head, I was turning the details of another artist’s life over and over, looking from every angle I could imagine. I would say it was the solitude, and the aesthetic beauty that I found on the olive farm, that freed me to do that.

The hardest part was leaving. Back to the world of interruption! I keep photos I took, framed on my desk. This helps me get back in the zone: the revealing, romantic, fugue state I feel so grateful to have experienced.