IZHAR PATKIN The Making of The Black Paintings

April 18–May 31, 2020

To Whites every Black holds a potential knife behind the back, and to every Black the White is concealing a whip. We were born into this dialogue and to deny it is fatuous. Our responsibility is to overcome the sins and fears of our ancestors and drop the whip, drop the knife. In Izhar Patkin’s parable of racial cannibalism we see that when a man with a .45 meets a man with a shotgun I guess the man with the pistol is a dead man.

Genet’s play was written for a black cast, partly in whiteface, to perform for a white audience, and Patkin’s stenciling carries this idea perfectly. His use of Olympia’s black maid, as well as Olympia herself…extends Genet’s paradigm of political colonialism to encompass cultural colonialism, inferring the status of blacks in white culture.

Genet is my Michelangelo.

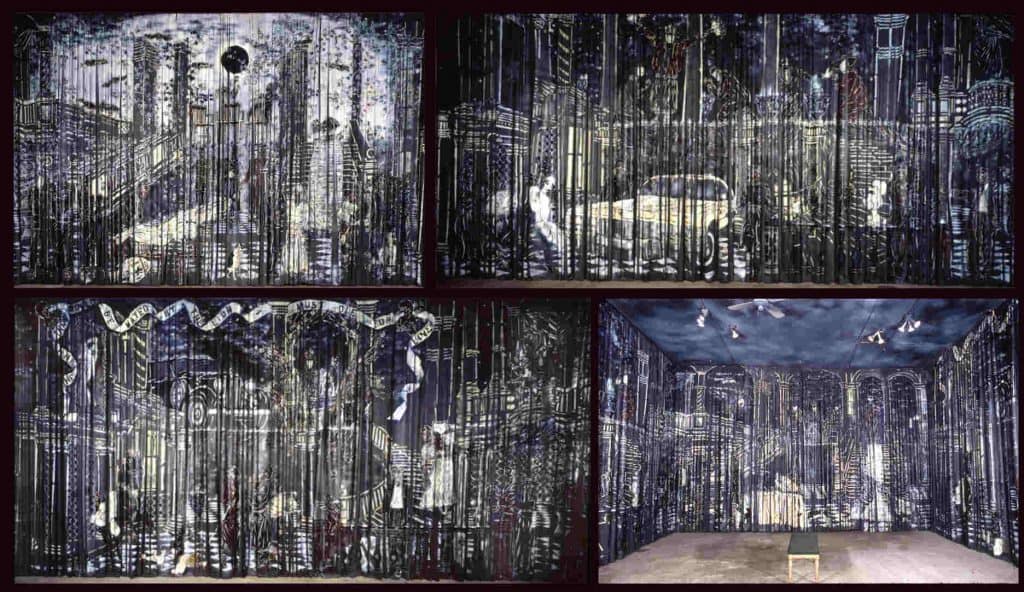

Some Serious Business and Howl! Happening are pleased to present Izhar Patkin: The Making of The Black Paintings. Izhar Patkin’s virtuosic The Black Paintings (1985–86)—a painterly adaption of a play by Jean Genet—is one of the most significant and inventive works to come out of the East Village in the 80s. An immersive room-size piece painted on black neoprene-rubber curtains, it expands upon the conventions of painting itself and also upon narrative, metaphor, installation art, and theatricality. The paintings, measuring 22 x 28 x 14 feet, were first exhibited at the Limbo Gallery in 1986. There, literally inside the painting, creators like Lydia Lunch and Charles Busch staged iconic, cutting-edge performances. The Museum of Modern Art acquired The Black Paintings in 1988, and they were shown at the Whitney Biennial in 1987 and last exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in 1990.

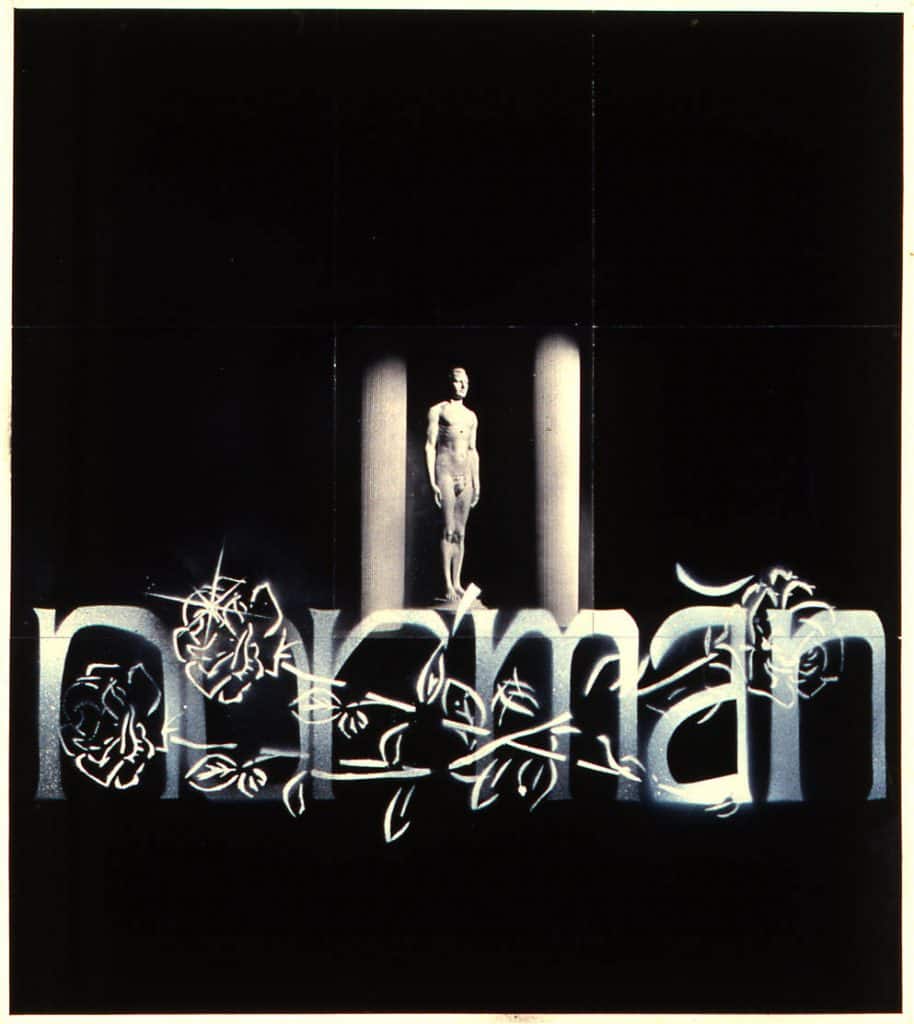

The show is not about re-presenting The Black Paintings themselves, but rather concentrates on the development of Patkin’s visual vocabulary culminating in the painting. The exhibition also includes two earlier related bodies of work: Norman: The Average American Male, 1981 (Collection, The Jewish Museum, NY) and The Meta Bride, 1982-83 (Collection, Whitney Museum, NY). The installation concept—A Performative Archive—will contextualize the art with interviews, writings, and ephemera that highlight the conception of The Black Paintings and its precedents, and animate the ideas of two groundbreaking writers: New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp and art critic Edit DeAk—treasured friends with whom the artist shared ideas and reflections during the making of these works.

Having immigrated from Israel in the late 70s, these early works were Patkin’s way of sorting out the terms and mythologies of his new American homeland. They manifest and respond to issues vital to the artist at that time—the death of formalist painting and the birth of identity politics; the return of narrative; and the upsurge in performance, installation, and time-based art. The exhibition showcases the centrality of storytelling and metaphor to his work and is motivated by his emotional response to and keen observation of mainstream American culture. “Metaphors create identity. They are the DNA of language, predictive of hereditary cultural diseases,” he asserts. “We live in the age of correction, but we need reinvention. As an artist, just dealing with anecdotal politics in my work wasn’t an option. All that is normative must be examined at its roots, including the constitution of paintings. English is a white Christian language. The deep doctrines in language itself are something I had to address,” Patkin adds.

Curated by Susan Martin of Some Serious Business with Howl! Education Director Katherine Cheairs, this timely exhibition is meant to underscore Patkin’s singular visual inventions, which he employs to critically unpack the prejudices he sees as deeply rooted in the norms, conventions, and default settings of our collective metaphorical language.

“Artists have always been in the forefront of social and cultural innovation. It’s through invention that the artist has agency in the world,” says Martin. A catalog contextualizing the exhibition will include new essays by philosopher and cultural historian Kazembe Balagun, curator and historian Chaédria LaBouvier, cultural commentator Carlo McCormick, and art historian Sarah Wilson of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, as well as writings from the 80s about these early works by Maurice Berger, DeAk, and Muschamp. Public programs include panel discussions, a Genet seminar, film screenings, and other events with fellow artists, writers, and activists intended to contextualize the works and invite dialogue on the state of conversation in contemporary art, and the ontologies of race, identity, and cultural programming.

BODIES OF WORK

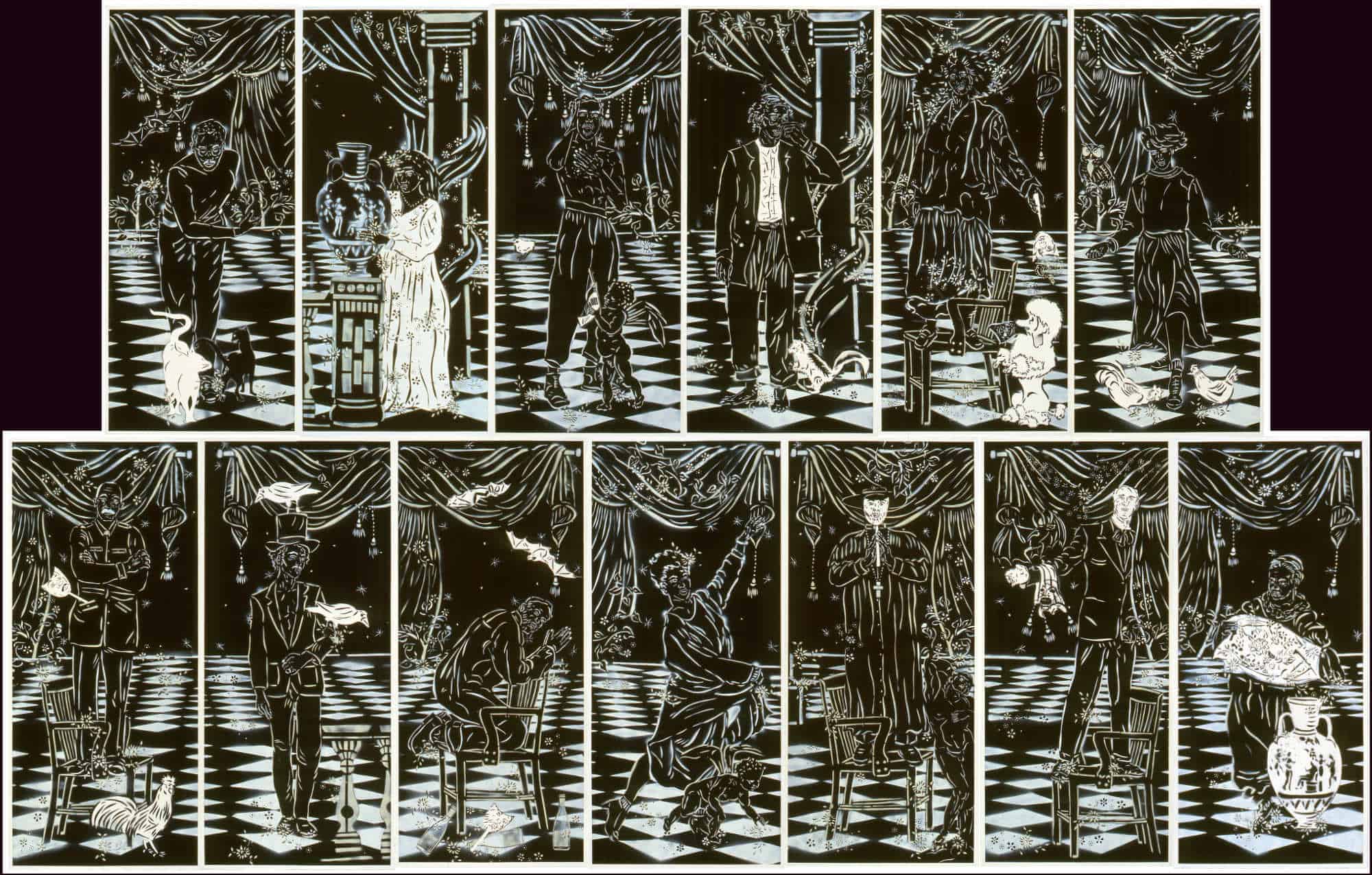

13 stenciled collages on black chrome-coat paper, 93 x 42 inches.

The paintings in MoMA’s collection will be represented by life-size portraits of the cast of characters: Each collage is linked with a quote from the character in the play. Of the 13 principal characters in Genet’s play, 10 of the collages were modeled on Patkin’s friends. The other three are Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer; The Meta Bride; and Laure, the black maid in Manet’s painting Olympia.

Patkin adapted Jean Genet’s The Blacks: A Clown Show as a narrative device for paintings that tap into a wide range of visual metaphors challenging the binaries of black and white. Patkin was drawn to the play because, as he says: “When Genet asks: ‘First of all, what’s his color?’ he questions and inverts these artificial dualities. I felt Genet was painting the play, not just writing it. As a painter, I don’t use black as the opposite of white. They are colors among colors. With Genet as my dramaturge, The Black Paintings were my way to repudiate how these binaries are encountered in language and everyday life.”

Written for Belgian director Raymond Rouleau’s all-black theater company, The Blacks was first performed at Le théâtre de Lutèce in Paris in 1959. The play comments on the supremacist ideologies that underpinned colonialism—its black characters trapped within negative perceptions of blackness while the whites are caricatures of imperial cruelty, of “whiteness.” First performed in New York City at the St. Mark’s Playhouse in 1961, The Blacks was the longest-running off-Broadway non-musical of the decade. Directed by Gene Frankel, the cast featured James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett Jr., Cicely Tyson, Godfrey Cambridge, and Maya Angelou.

Among the ironies of The Blacks is the fact that this protest against the white world was itself written by a white man. Genet’s ability to identify with victims of prejudice owed much to his own identity as an orphan, a homosexual, a thief, and a convict. Genet’s grievances are contained within a highly disciplined art form and channeled through humor and constant inversion. In the play, as in The Black Paintings, the audience is inherently a key “actor.”

This play, written, I repeat, by a white man, is intended for a white audience, but if, which is unlikely, it is ever performed before a black audience, then a white person, male or female, should be invited every evening. The organizer of the show should welcome him formally, dress him in ceremonial costume and lead him to his seat, preferably in the first row of the orchestra. The actors will play for him. A spotlight should be focused upon this symbolic white throughout the performance. But what if no white person accepted? Then let white masks be distributed to the black spectators as they enter the theater. And if the blacks refuse the masks, then let a dummy be used.

—Genet’s prelude to The Blacks

For Genet, writes Neal Oxenhandler, “blackness is the hallmark of all those who suffer exclusion, deprivation, degradation; all those who are oppressed, minorities of all kinds, men of all castes and classes; homosexuals and thieves as well as black and Jews; women; and those whose role in society is to realize themselves as outsiders…” 1

In a review of The Black Paintings, the poet Hezy Leskly commented on the connection between the work and the audience: “When you walk into The Black Paintings, you are A Community.” Herbert Muschamp had a similar experience stating, “I thought the power of the show lay not in the cease-fire of the battle between black and white, but in the collapse of the dualism between self and environment [other].”

Tulle-veil painting, 9 x 8 feet, and video of Meta Bride performance

Exhibition Copy

Collection, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

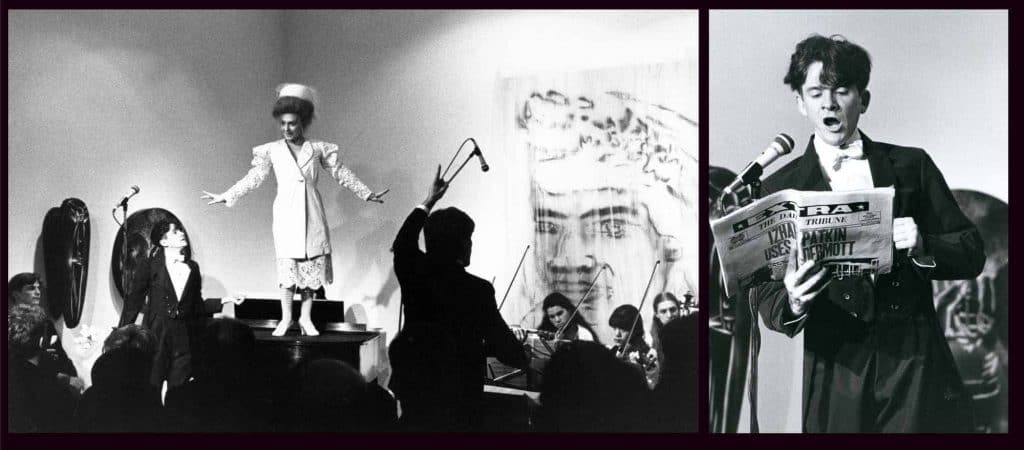

Patkin’s first veil painting ever exhibited, The Meta Bride was the centerpiece of an exhibition at the Holly Solomon Gallery in 1983 that mixed performance and paintings. Patkin’s meta[phorical] bride was inspired by a discarded photo he found on a New York City sidewalk of an African American bride in her white wedding veil.

The exhibition closed with an Easter Sunday “marriage” oratorio featuring David McDermott as the groom and contortionist Ula as the bride. Accompanied by an orchestra and wearing a black rubber tuxedo by Sally Beers, McDermott sang a Gershwin-like, soulless rendition of Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message”. The performance culminated with McDermott singing “I Do”, written for the occasion by Kristian Hoffman, while on the piano Ula evoked the athletics of breakdancing—twisting herself into a cubist-like sculpture attired in a white leather and Calais-lace wedding gown by Diane Pernet.

“Neither ridicule from a sophisticated campy stance, nor political propagation of a corrupted social norm, it is a genre play,” says Edit DeAk writing in Vogue Italia, September 1983. “Izhar throws himself a wedding-party spectacle, mixing thematic elements about marriage in a pancultural synthesis of the marriage ceremony. Producing this spectacle brings his two- and three-dimensional work into the fourth dimension of theatricality. He is making a spectacle in the tradition of painter’s theater.”

Six paper collages and a pinball machine

Chrome-coat paper, photo prints, enamel spray paint; size variable

Collection, The Jewish Museum, New York

Meant to represent the average American male and female, “Normann” and his female counterpart “Norma” were created by gynecologist Robert Latou Dickinson and sculptor Abram Belskie. They were first reproduced in Harry L. Shapiro’s article “A Portrait of the American People,” Natural History magazine, June 1945.

Maurice Berger writes in the catalog essay Race and Representation: The Production of the Normal, Hunter College, 1987:

A model of “normal” perfection, his name is, appropriately, Normann. And along with his perfect sister Norma, he stands as a testament to the “character” of the American nationality… Patkin’s Norman resounds with juxtapositions that shatter the complacency of Normann’s perfect world. Posed in a range of passive positions—standing, sitting on a chair, sitting on the floor, crouching, kneeling, sleeping—Norman is now vulnerable; he is robbed of his pedestal and his fig leaf, the affectations of artifice and purity that had signified his social removal… To respect what is recognized as normal is to belong to that comfortable majority which lives at society’s center. To live outside this center is to exist at “risk.”

A PERFORMATIVE ARCHIVE

The ‘Performative Archive’ narrates and connects the dots of both the material and the subliminal making of The Black Paintings and its precedents. Delineated by exposed aluminum studs creating open wall-less rooms, the installation uses scaffolding as a device and metaphor to present the archival material in a state of becoming. As the viewer journeys from one “chapter” to another, they experience the development and “becoming” of The Black Paintings through preparatory drawings, photographs, catalogs, books, recordings, and other ephemera.

Howl! Happening: An Arturo Vega Project

6 East First Street (between Bowery & 2nd Avenue)

New York, NY 10003

(917) 475-1294

contact@howlarts.org

Gallery Hours: Wed–Sun, 11–6 PM

1 Neal Oxenhandler, Contemporary Literature, University of Wisconsin Press, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Autumn, 1975)