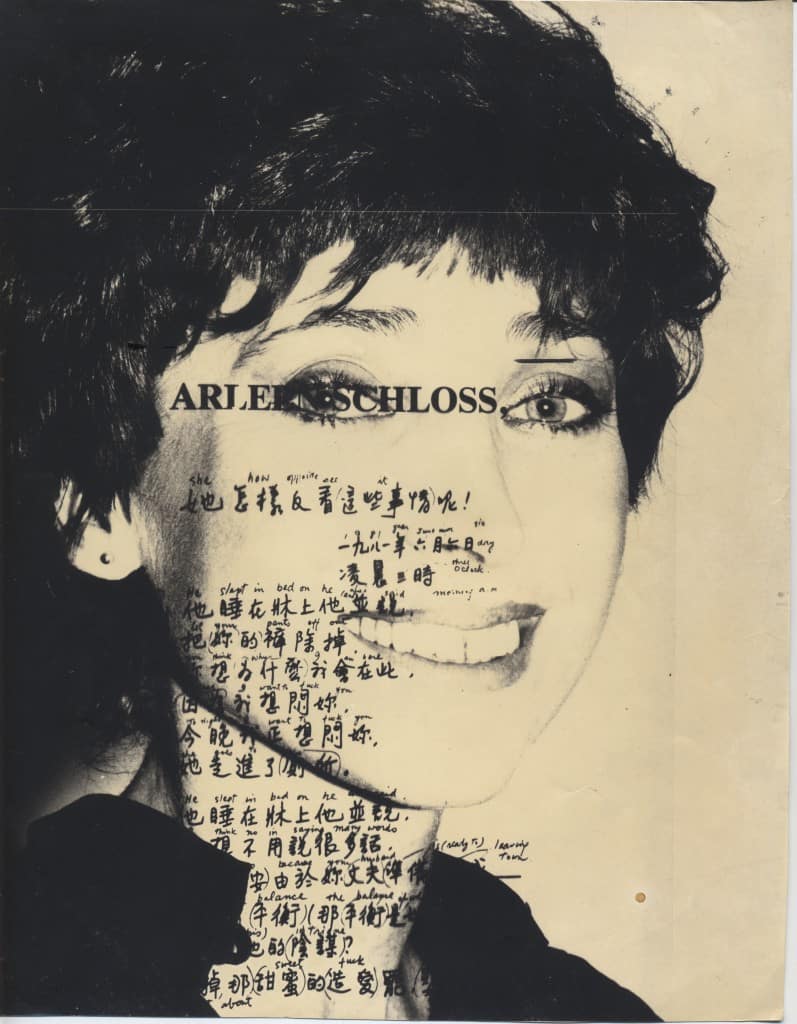

When I first met Arleen, I was little known outside of what I had exposed of myself within the downtown art scene of Lower Manhattan. I was a Black queer kid stalking Buster Cleveland and living with Tim Greathouse, my roommate. As I grew into some renown and celebrity in the 80s, as co-director of a prominent East Village gallery, Arleen was traveling with Glenn Branca in Europe and later working in residence at Ars Electronica in Austria. I don’t recall the time line of when she returned, but do recall visiting an art camp in her loft in the 90s – her loft had become a hostel for artists, a wayward station once they had landed in New York.

So much had happened in our lives from when we met in 1979 and occasionally running into each other at events over the years. We didn’t come back into regular association until decades later in 2000. By then she had been diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. I would visit and hang out with Arleen at the back of her loft, walking back through shelves of video tapes, recording and sound equipment, stacks of ephemera, catalogs and file boxes, wondering: what’s going to happen to all these materials?

Arleen lived on the second floor of a 5-story loft building at 330 Broome Street just east of the Bowery. She, along with a group of artist friends, had purchased the building and each had taken a floor and formed a co-op that would be named using an anagram of their first names (a detail less important to this story.) They would hold events in their loft spaces and the elevated courtyard that expanded the second floor that Arleen occupied. These loft space events (some would become known venues) were something that was common in the area for anyone familiar with the landscape at that time.

Revisiting my life on the East Village and the Lower East Side in 1979, it was around that time that I met Arleen. We were more observant in those days. Flyers were posted and sighted everywhere promoting events. If newsworthy enough, events would be listed in the SoHo weekly News, the Village VOICE or in the new appearance of the East Village Eye. We were very curious social creatures finding our way through unmonitored social engagement and activities that we would engage in. Our activities were not recorded with cell phones and propagated as they are today. Experiences could not be connected vicariously through the Internet. Payphones and landlines did the trick.

As a young aspiring artist in my 20s I’d already found some like minded people tracking Lower Manhattan’s territories on my daily adventures heading out from my rented apartment on St. Mark’s Place that I’d moved into the previous year, half a block west of Tomkins Square Park and a block east of Club 57. I was working as a framer at a print gallery on West Broadway at Spring Street next door to the Phyllis Kind Gallery around the corner from a sidewalk art gallery that Buster Cleveland called the Office. The Office was where Buster Cleveland would hang out with his portfolio of color xeroxed editioned sheets of artist stamps and collages that he would sell to interested collectors. He’d print these editions with Tod Jorgensen, who ran the color Xerox machine at Jamie Canvas down the block on Spring Street.

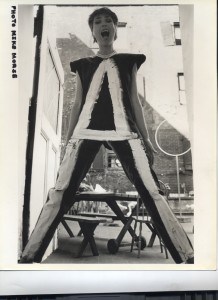

Tod Jorgensen also xeroxed flyers announcing an event called Wednesday at A’s that he would organize with Arleen. The flyers appeared all over SoHo, and the Lower East Side announcing a program of performances that would take place in Arleen’s loft at 330 Broome Street on Wednesday night’s for $3. These events were a platform for familiar and unfamiliar appearances by local and international artists, would be artists, musicians, poets, actors, and filmmakers — known, unknown, or just discovering who they wanted to be. They came from everywhere. It was totally democratic in nature, intersectional and international. If you were up for presenting you would be announced on the flyer and present what ever you had to present. No auditions or formal proposal was required. Experience or track record didn’t matter. You could totally invent yourself as anything and present however you wanted to present and see what would happen. A lot happened, the best and the worst of it.

The events became an incubator for the experimental and what it created was like nothing else because of its classless nature. A lot of people mixed, participated, and experienced what performance art could be for the first time. Expectantly, I became one of the participants as a one-time solo act and on occasion in collaboration with others. Arleen held performance art workshops in her loft for years before her Wednesday’s at A’s project began, co-hosted with Tod Jorgensen. I would see Arleen at these events and other locations. The Rivington School of metal workers would never have found their home in that neighborhood had it not been for Arleen. She was also a participant in a lot of activity at NoSeNo, a sectional community that circulated around Wednesday’s at A’s. Most remarkable in all this was that Arleen was videotaping and sound recording all of it as is evidenced in the hundreds of video, super-8 and 16mm film, audio and digital files she stored in her loft.

What Arleen managed to accomplish and preserve in all this is extraordinary and what brought me to necessitating having it preserved. The impetus initiated in a conversation visiting Arleen, smoking refer, and listening to her concern with being lost and forgotten with her inability to be out there as she once was due to managing her Multiple Sclerosis.

It wasn’t until 2014 that I began discussing this archiving concern with Arleen. Stuart Ginsberg had already been working with Arleen on a documentary film project to preserve some of her important legacy, but what of the actual archival materials? It was quite clear to me that the best way to start and get some overview was to catalog her flyers. It was through this process and spending more time with Arleen that made me recognize how important the task I had taken upon myself to complete was.

I cataloged the 189 flyers that were deposited in the Downtown Collection at New York University’s Fales Library under my direction. Soon after this was completed Arleen had an accident that had her suffer a brain injury that incapacitated her functioning even more and brought me into a situation where I became an assistant to her care and rehabilitation. In doing so it became ever more pressing to begin preserving the remaining materials in her archives having me catalog videotapes, audio tapes, file draws and boxes of supporting material, journals and ephemera were organized for complimentary deposit in the Downtown Collection at Fales. All celluloid and super-8 film were deposited with the Anthology Film Archives, something the curators there were thrilled to have.

Since then, the super-8 material became an organizing project for Traci Mark, a young scholar, who wrote her thesis on her findings and research during her internship at Anthology. Curator Harry Burke, included Arleen’s alphabet and word works in his Works Off Paper exhibition in the Print Room at Saltz in Birsfelden, Switzerland — and now, this.