QAW: I have so many questions about your Moth Migration Project – at the moment poised between creation and culmination, since you are continuing to work on this project while you also exhibit it throughout the world. I am specifically curious about your intimacy with the moths themselves, and with the collaborators who are involved.

Let’s begin with your brain! You’ve said your compulsion for this project rests in the moth as a nocturnal pollinator. What is it about pollination – nocturnal in particular – that has driven you to set forth on this truly massive body of collaborative work? For such an ambitious collection – which bring to mind the 17th century European entomological practice of collecting moths pinned in frames and drawers – what underlying passion in your psyche has sustained this herculean task?

HL: I knew I wanted to work with moths. Moths conjure up an image of nighttime, lights, creepiness, and they are food for bears. I am a big fan of mammals. In seeing the gallery space I saw options of darkening the room, creating a nighttime “moth feeding” and possibly including a two story tall bear over the stairwell landing who would be consuming the moths. It is not only about pollination but it is the cycle of nature and would make a killer installation.

The concept of the exhibition is that “Cross Pollination not only refers to how insects and other creatures pollinate plant life, but also to the cross pollination of ideas in art and science.” I decided to focus on the cross-pollinate of ideas in art and science through the connection of people by crowdsourcing moths. I would use the symbol of the pollinating moth and ask people to contribute regional moths.

My ultimate goal is still 40,000 as that is how many moths a grizzly bear can eat in a day. So initially my passion was also to get as many moths as I possibly could in the time I had. Ultimately I got rid of bear as the crowd-sources moths poured in, it was far more interesting to follow the pollination of my idea as it moved between people.

QAW: So much of this is about density and intensity of the quantity of moths. And of course that means lots and lots of participants. The historical legacy of participatory art clearly lends itself to the more contemporary practice of internet crowd-sourcing collaboration.

Tell us a bit about your initial vision for the project, and how the involvement of hundreds if not thousands of collaborators has changed or affected, altered or redirected that individual vision?

HL:This has been remarkable. I put out a call for entries on my blog, which posts to FB, LinkedIn, Google+, the usual social media connections. I also send an email to my friend Gaye Patterson, an artist, printmaker and writer in Sydney, Australia. I went to bed, scared to death about what I just did. Will I look foolish? Will anyone actually do this? Will anyone even see what I wrote?

The next morning, I had 200 emails from people saying they wanted to do the project. It came from artists, entomologists, teachers, citizen scientists, a whole range of people. I hosted moth printmaking parties at my home, at Rush Arts in Chelsea, NYC, and a number of other locations.

I thought I had been very detailed in the instructions but there were loads of questions. So that meant I needed to clarify further, make sure the information was available. Within two weeks, I created an organizational system. Josh LaMore – a friend who is in library science graduate school at Pratt – came over and we set up a Google form, Google sheets, a new Gmail account and linked everything together to make cataloging as easy as possible.

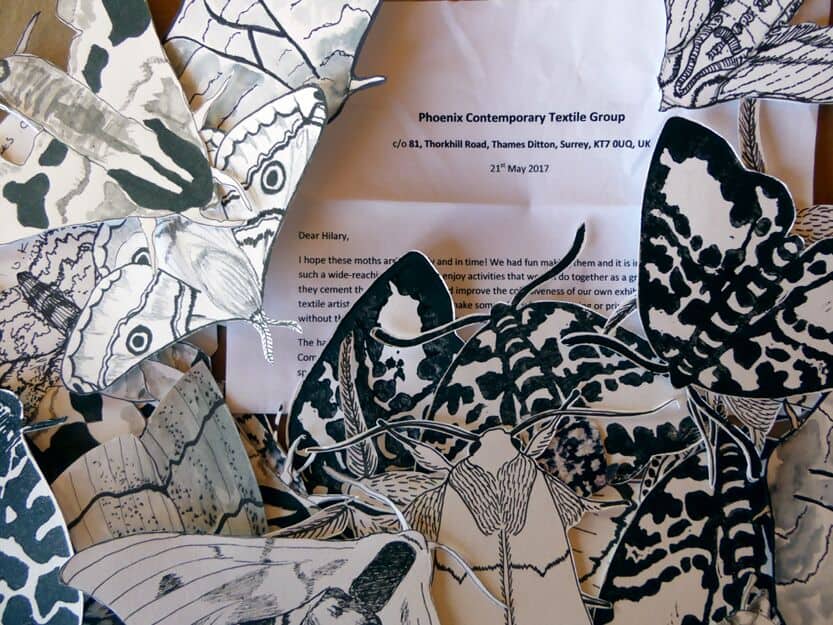

This was quickly becoming about digital management and daily correspondence with people, it was about communities. In February I got an email from a gallery in Kent, England. SevenOaks Kaleidoscope Gallery who host a yearly themed-based exhibition, they wanted to use my idea, but put their own twist on it. They would engage 19 schools and art centers to collaborate. Their exhibition titled, “Whispers” alluding to whispers of moths, included 1894 moths. I would see school kids and professional artists on Instagram, twitter, FB, making their pieces to contribute. The SevenOaks exhibition was beautiful and when it was over, they boxed it up and shipped it to me. Now all the moths are together in my Abiquiu, NM studio in awaiting installation.

By allowing people to take my idea and use it in their community, it has snowballed the reach and effectiveness of my idea.

A large number of teachers worldwide have used this project for the teaching of the environmental sciences. I would say the re-direction or perhaps real direction is that previously I wanted to take the exhibition to well known galleries and museums to elevate the project. I still want to do that, but now it is far more important to me to take the show to the places where people were most involved. I want to meet the contributors. I want to take this giant collection of moths to show each person how much their contribution mattered.

QAW: This is a fascinating connection between the creator in you and the individual creator that sends you pieces. Through the moths, you have created intimacy within a truly enormous number of participants. In your artist’s statement you mention, “through social media and interpersonal relationships, the moths become a symbol of community.”

How have you personally connected through these relationships? Pollination, as an act of reproduction, as an act of physical creation, is intimate by definition. What intimacies have you encountered through your shared process? Which intimacies have most surprised you, or upended your concept of intimacy? What is your essential approach to shared authorship as an act of intimacy and procreation? How does contemporary semi-anonymous crowdsourcing impact this typically intimate process?

HL: The first thing is that I personally email every single person who sends moths to thank them. I want to let them know their package made it though the mail. That may sound like a small thing but with hundreds of emails a day, it is very demanding. I also open each package, count the moths and comment on what I most liked about their moths.

This often created a great back and forth of emails. I set up a FB Group, this was a big success. Within a week we had 500 people from the project sharing their moths with each other.

Another component is I mailed a specially designed postcard to each participant. I hired one of my former students, Joanna Gonzalez and an artist friend Ginger Legato to each design a postcard. The postcards are amazing.

The artists who contributed moths are important to me and I needed to thank them each properly. In an age of poor communication, no communication or not acknowledging people for what they do, it is very important for me to acknowledge every thing person. I did that with the postcards.

Another beautiful surprise was the outpouring of help and support from friends in Abiquiu, New Mexico. Not that I doubted anyone, but I am so used to working alone and doing everything for myself, I didn’t think people would be interested. But it was amazing. So now, I also have a community in my studio helping to sort, catalog, and stamp. It was so nice to have my studio full of friends.

Working in a community is a totally new way of working for me and it is so rewarding.

QAW: I suppose the human word for this is community, but I should have been using the moth terminology! Or rather, the human terminology for a moth community! A group of moths is called “a miller of moths” – drawn from the phenomenon of moths gathering around a light source.

The Moth Migration Project exhibition includes all the names of the participants, thus expanding authorship of the project to the participants beyond you as sole author. Does this make you the light? or part of the miller? Because you have been crowdsourcing to other for the production of the work, you have become representative of all your participants – this is an uncommon role for most artists. How has navigating being the light source or being part of the miller surprised your process? What conundrums are you facing when representing yourself and other artists’ work simultaneously?

HL: Oh, your questions gave me shivers. Boy, would I love to be the light, but it sounds too egotistical and I am not comfortable with that. But I sure would like to try that role on, let me sit with that a bit.

I do feel a responsibility to all the artists. My list of individuals is 17 pages long – in additional I have pages of organizations where I have no idea who many people contributed. I want all their names to be seen, but this is a problem in any gallery, how do you show that?

Also most recently I learned the space I was allotted was reduced. The contributors made moths – in some cases as many as 200 – believing everything would be shown. It was important to me to let them know that it is impossible to show everything, this time, because there are over 14,500!

But I am proposing this exhibition to large museums, and it will travel. I plan to keep all artists informed about what is happening with their contribution.

So as with all light, it dims, it shines, it moves and it evolves.

QAW: Indeed – and thank you for pointing out that all creative processes involve that process of movement and transformation. Another reason moths are such fertile metaphors, as well as phenomenal creatures.

I saw that you were up to 2,846 moths in April, what is the grand total now? Can you include all the moths in the 516 Arts Exhibition? How are you navigating sharing authorship and representing every participant in the confines of a limited gallery space?

Since you are not the only maker in this project, how do you navigate authorship, ownership and agency of the work that is produced in collaboration with others?

HL: On the deadline of July 15, we had 14,563 moths. But of course more are coming in every day. I only have about 40 foot length of wall chopped up into 5 sections, however I will use the ceiling too. This is less than half of what I thought I had available in terms of space, but it is a large group show and things shift.

My goal is to show at least one moth for each person, so that all are represented.

As for authorship, I own the idea, the entire crowd sourced project, however each artist is a collaborator and each artist is integral to the whole piece. In addition to the exhibition, I hired a visual data web programmer, Ellen Manuszak, to create a website tracing the origins of all the moths. At first it will list each city and town with the number of moths, but eventually it will list each person by name or organization and have an image of their moth. It is a large and expensive undertaking so it will happen in stages.

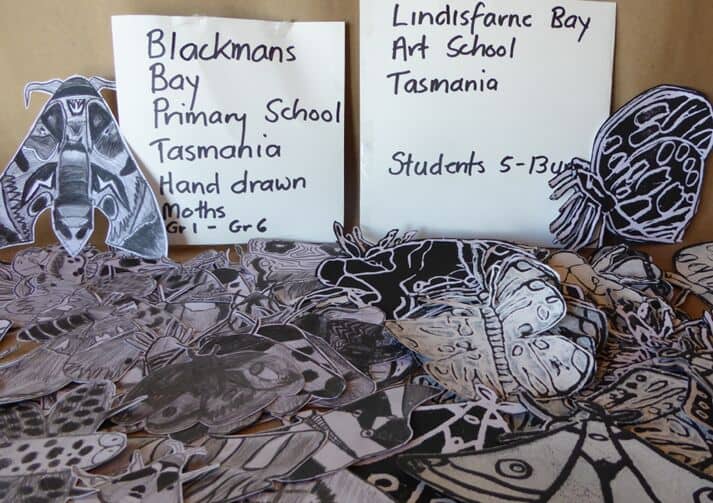

QAW: You have received many multimedia moth prints from students who were introduced to the project by their teachers…most of whom I understand to be strangers to you at the beginning of the project. When you began this project did you expect such an enormously enthusiastic response from teachers and students? How has this affected your own idea of youth as artists? How has the involvement of youth impacted the project? How has the project impacted the youth participants?

HL: It never crossed my mind that school would pick it up. One teacher in particular Bernadette Knight, an Art Specialist Teacher from Palmyra Primary, Palmyra West Australia, had 450 students. In three months, she had all 450 kids make 10 moths, 4500 moths, some of which they sent to me, others they kept. This is what Bernadette had to say:

“I involved the kids and parents in my school community because I thought this project was a great authentic task through which I could reach the whole school community and teach a variety of printmaking processes but also because it illustrates beautifully how the arts can enhance learning and communicate ideas across other learning areas, like science.

Many people believe art and science are incompatible but I believe there is an overlap as this project clearly shows. In an educational climate that is pushing STEM subjects its important not to forget the role and importance of the Arts in enhancing learning and communication in these subject but also for the learning and benefits of the arts in their own right.”

QAW:This projects seems to be exponential! Do you plan to continue producing moths with others? Is there a culmination – in terms of process, practice, production – that you are hoping for?

HL: Ah, a culmination, maybe 5 years down the line.

My next goals are to get the exhibition to every town or city where a large number of people participated. This might be a major city or an remote village. It is a matter of my conscience that those who made the most moths deserve to have the show come to them.

But as the artist behind the project I want to see it huge, I want to see it, quite honestly, at the New York Natural History Museum. That would be a fine culmination. I want to have a giant hall that is covered with all the moths and a separate area with tables where people can see all the ephemera that was included in people’s packaging; letters about being citizen scientists, news clipping about moth habitat destruction, handmade books and boxes with quotes and photos of people coming together to make moths.

I want it to be an experiential multi-sensory installation of international moths that is not confined to an art venue but in a venue that is visiting by people of all interests, just like the Moth Migration Project. It is people coming from a variety of interests and backgrounds who created who contributed to its success and I think it should be shared in the same manner.

For more information on The Moth Migration Project, visit Hilary’s website.