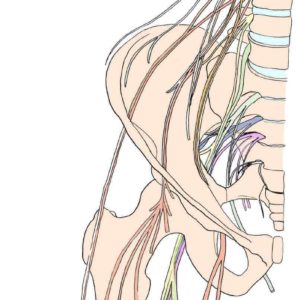

Some Serious Business is pleased to announce a collaborative SSB Away residency with yoga therapist Deborah Wolk and artist Kimberly Reinhardt. A yoga specialist for musculoskeletal, hormonal, and nervous system imbalances, Wolk also teaches and studies anatomy. She has been recognized for her work with scoliosis and founded a yoga center that is a workers cooperative specifically geared towards therapeutics. Reinahrdt has a broad range of interests including the links between healing and sustainability. This has led her to practices and areas of study including yoga, anatomy, kinesiology, composting, and urban gardening and farming.

In the process of collaborating on a book on yoga, scoliosis, and the nervous system, Wolk and Reinhardt realized that the therapeutic issues of her students related strongly to a disconnect with the body—but also with the earth.

“Through daily walks in the desert, Kim will paint, and I will write about the relationships we see and sense between the structures and functions of the human nervous system and our relationship to the energetic systems of the beings and matter that make up our environment,” says Wolk.

Through this collaboration, they intend to create an artist’s book with a visual and poetic narrative that knits together the structures of our nervous system as mapped out via literal dissection, with a felt sense of the landscapes and world around us. For a deeper vision about how each of them navigates their personal and artistic lives, we asked them to answer a few of our #FiftyQuestions.

Deborah Wolk and Kim Reinhardt #FiftyQuestions

In thinking of the lulls and gaps or lost places in your practice over the years, who or what has re-energized you?

DW: My yoga and anatomy teacher Genny Kapuler and the process of studying anatomy.

What is your current guiding motivation to work and/or express yourself?

DW: The more I understand about myself through my practice, about all living things through my study of anatomy, the more I am excited about how much more connected I feel with everything around me. What was once dull has created an environment which endlessly sparks my imagination

Do you have a relationship with the distant future – in other words, are you making artwork that bears a message or impact for coming generations?

DW: I’m not sure about the existence of coming generations, but I hope to have a message which will help those around me see where and who they are right now.

What role does your genetic or cultural background play in your practice?

DW: My parents and their families had a strong attachment to religious and cultural Judaism. The posture of Judaism is that of kyphosis: the torah reader and davener being the most accessible image. Jewish women are said to be the only genetic group that develops true osteoporosis, so the idea of the bent over, delicate boned, unathletic Ashkenazy Jew runs strong through my family and cultural background. I have spent the past 25 years actively working to prevent the “inevitable.” My mother had broken both hips by the time she was my age and broke them many times again later in life. So happily there is also epigenetics—my bones so far, have remained strong.

KR: My mom who passed away suddenly in 2015 was an artist. She went to the high school of Music and Art in NYC and then later Carnegie Mellon and MICA. She taught art in Baltimore City Public Schools and in a prison for children tried as adults. She was a small person physically but had a lot of courage and spark and created several murals in the city when I was growing up. My older brother was also an artist and went to Cooper Union in the late 1980s. I remember coming from Baltimore to visit him with my parents when I was a kid. Walking around the East Village, hanging out with the Cooper shop techs, and staying in the various spaces where my brother lived was very influential. I ended up going to Cooper Union in the ‘90s. Though my family was very artistic, there has also been a lot of trauma and drama. Many of these events happened way before I was born, and the result was that I grew up not having grandparents or any other close relatives. The past was never really talked about, so I tend to feel a bit like an alien. Connection to plants and the natural world as well as a yoga practice and study of anatomy has helped to ground me.

What surprises you most about what you are doing right now in your practice? If the nine-year-old you could see you right now, what do you think they would think?

DW: My life has taken so many twists and turns. All of it would have surprised that child who originally wanted to be a sustainable farmer in Vermont writing books in her free time (free time on a farm!). After 20 years of making visual, installation, and performance art and working any kind of job I could get in NYC I became a yoga teacher almost by chance. I had no goal to be one, I never wanted to run a business, I was not interested in working with the general public. Yet, working with and helping to heal others with what I’ve experienced, seeing people change on every level when they do the work, has made me happier than all the other paths in my life.

KR: My nine-year-old self would think: “How cool is it that you get to spend time in the desert of New Mexico for a couple of weeks and work on a collaborative project about the nervous system and nature.”

What is your working relationship to loss? Either personal loss, or lost works of art, or other kinds of loss?

DW: The (paraplegic) teacher Matthew Sanford once asked, “who were we trying to save with our work.” I lost so many friends to AIDS and related issues like suicide and drugs in the 1980s and early 1990s and I was so young then. Some of those people were experimenting with holistic health techniques to prolong and revitalize their lives. Their experiments with macrobiotics, yoga and Zen made a huge impression on me and so I eventually became involved in those activities. Bit by bit these practices changed me and improved my life. I owe my work and outlook to these friends that I lost.

KR: My working relationship to loss is understanding how to not let it keep me from living.

When does Joy tend to visit you?

DW: With a synapse. There’s that moment where you make a connection — a mix of energy, intellectual and/or heart-oriented enlightenment that brings joy. It often occurs at the end of a project or when others visibly connect with my work.

KW: When I can forget the story line and find the synaptic gap.

If you could amplify a specific sense, which would it be? If you could minimize a specific sense, which would you choose?

DW: I would like to amplify and balance my sense of touch. Touch and pain have separate nerve pathways and the nerve pathway for touch is disorganized, disoriented, and out of balance with scoliosis. Strangely, even though sight is my strongest sense, online activities like Instagram, TV, etc. all can make me weary. COVID made it worse by moving so much activity to screens. When I’m in New Mexico I love to stare at the Mountain across from the dining room table. The only thing I see is the light changing…every second! Instead of feeling like vision, I feel like I am hearing the mountain. I would love sight to possess this synesthetic quality all the time.

KR: I am often frustrated at the way modern culture dissects disciplines and experiences. I think of the senses as crossing boundaries, fluid, and always shifting.

Have you ever had a physical illness, event, or impediment that has changed how you make or approach artmaking? And how?

DW: This is what informs all of my work as a teacher: my scoliosis, hormonal issues, musculoskeletal pain, surgery, and the subsequent emergence of a chronic autoimmune disease. The more I learn about healing these issues through my practice, the more I can share with my students…especially as they age!

If you could create a new public institution for your field, what would its mission be?

DW: I did this! With Samamkāya Yoga Back Care & Scoliosis Collective, a therapeutic, worker-owned yoga studio. Our aim is to make yoga accessible and healing to students of all ages and abilities who are living with back injuries, chronic/acute pain, differently shaped spines/bodies, scoliosis, and spinal fusions. In addition to offering highly specialized therapeutic yoga, we are unique in our business structure. We are the ONLY studio operating as a worker-owned cooperative in Manhattan dedicated exclusively to back care and scoliosis that is owned and run by our teachers. Our cooperative model allows us to build a collaborative co-created environment with fair wages for our highly trained and talented teacher community.

KR: Create affordable, accessible alternative energy infrastructure with a focus on closed loop waste streams.

Do you have a particular skill or knack of which you are most secretly proud? Something you feel you can do that few others can, no matter how small?

DW: I can see asymmetry in the body more clearly than almost anyone else I know. I can also explain how I see it.

If you could be anything besides an artist in human form, what would you like to be?

DW: A long-lived tree in an ancient forest. I would like to experience the world with time slowed down so much that the human day would seem only like a moment. I love the idea of connecting, communicating and sharing water with my fellow trees through my roots and with the local biome through my canopy. My trunk over time would fill with various birds, animals, fungi and insects. A long, collaborative life.

What project of yours do you personally consider your most satisfying, and why – regardless of external support or accolades?

KR: The screen-printed bandannas I have been making are the most satisfying at the moment. Creating something tactile and functional, intimate, and sensual is very satisfying.

What is your current guiding motivation to work and/or express yourself?

KR: Being an artist is what I am supposed to be doing with my life. I wish it was not so connected to concerns about survival and livelihood but am trying to make my peace with this and accept my awesomeness instead of running from it.

Do you have a relationship with the distant future – in other words, are you making artwork that bears a message or impact for coming generations?

KR: There is a phrase that I heard the writer Donna Haraway say recently in an interview, “Can Yet Be, Is Not Yet”. I read this as a kind of circular mantra. I think a lot about what my role might be as a bridge or transitional human being between this world that is collapsing and the one that is yet to come. I believe how we show up at this moment and where we direct our attention is very important. Being able to feel my feelings, respect grief and also keep reaching towards expansiveness, interconnection and pleasure are guideposts in a culture climate that monetizes and weaponizes a rotating cycle of crisis. Adriene Marie Brown and earlier activist Audre Lorde’s writing about pleasure activism are important voices for me that help counterbalance the fear and aggression that the dominant culture pushes us towards.