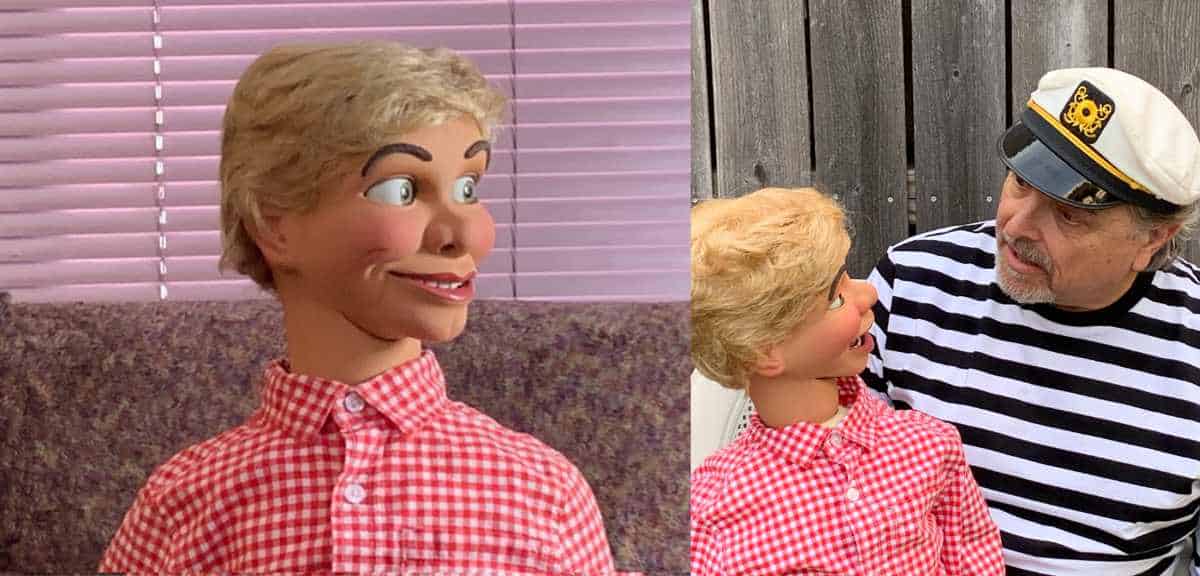

#SSBAWAY is pleased to welcome writer and director Kestutis Nakas—and his ventriloquist dummy Peanuts—to Plaza Blanca for a residency this month. While in residence, Kestutis will be writing and editing his newest work with Peanuts. In the trajectory of this performance work in progress, Peanuts is a tyrannical, domineering figure, wielding power over a captive ventriloquist who must find a way to restore the balance of the universe.

What event or factor in your life has been the most pivotal in your decision to become an artist?

I was a “rock ‘n’ roll-hippie wannabe” at age 17 when I hitchhiked from my home in Pontiac, Michigan, to Los Angeles. I had many adventures, including being taken to a Navajo-only dance way out on the res and traveling up and down the Pacific Coast Highway. But when a cousin took me to a double bill of Fellini’s 8½ and Tod Browning’s Freaks, it exploded my consciousness out from its 60s countercultural orientation. I saw that rather than getting locked into any one cultural stance, I could open my mind to any vision my imagination would allow, no matter how “weird.” I resolved then to become a filmmaker. That morphed later into other things. What matters most is that, at that moment, I made my first active decision to follow an artistic path.

What artist do you consider most influential to your ongoing development as an artist?

Jeff Weiss, for brave devotion to his personal vision. He was (and is, late in life) the embodiment of Grotowski’s “holy actor” in a “poor theatre.” From his youth, he pursued his over-the-top theatrical fabulousness with ascetic conviction. His is the purest life in art I know of, the “north star” I navigate by but will never reach.

What has been the most significant challenge you’ve overcome to continue your art practice?

Kicking booze 33 years ago.

Describe your ideal workspace.

A place of solitude with supportive and creative friends nearby.

Which one sentence do you hope describes how your art practice will be recorded in history, and why?

Although like most artists I will probably remain obscure after I die, it would be nice if the work remained meaningful across time.

In thinking of the lulls and gaps or lost places in your practice over the years, who or what has reenergized you?

Immersion into an unfamiliar environment or activity.

What project of yours do you personally consider most satisfying, and why…regardless of external support or accolades?

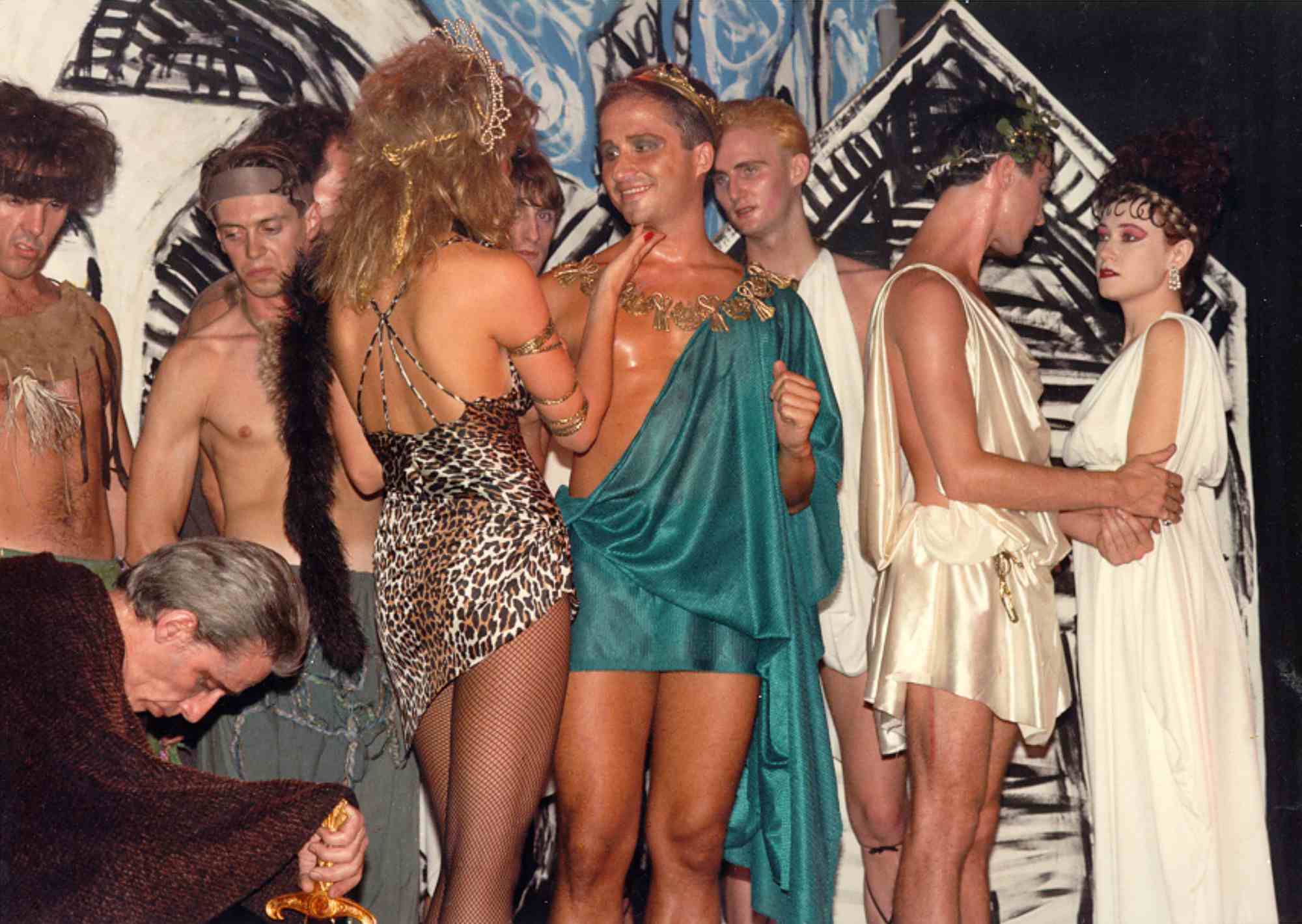

In 1983 I directed a production of Titus Andronicus at New York City’s Pyramid Cocktail Lounge. It was a synchronous coming together of the right people, the right play, the right space, and the right audience. Everything about it was magic, and it was very much a communal project coming out of the explosive energy of the Pyramid in those days. All the artists involved worked hard, took huge risks, and became transmitters of a high-voltage creative current that ran between them and radiated out to their surprised and (mostly) delighted audience. I originally meant to end my pursuit of theatre with this project, but instead it became a new and satisfying beginning.

If you could travel in time, within what era or milieu would you most like to have an artist residency? And why?

Elizabethan England. It was an upstart, newly Protestant nation, coming late to the Renaissance under a female monarch, the “virgin queen.” Against all odds, they scored a major victory against the most powerful navy in the world, the Spanish Armada. Their spoken language, early modern English, was probably at its most dynamic stage in history. People drank beer at breakfast and sang in the streets, between plagues anyway. London was a city of 200,000 and yet they were making theater that would endure for centuries. Theater (including Shakespeare) was a popular art enjoyed by all levels of society. It was a time of expansion, with the feeling that anything was possible, although the consequences of colonialism are still painful today.

What is your current guiding motivation to work or express yourself?

Making and performing original performance art is a life practice that allows me to rediscover myself and the world around me and communicate that discovery to others, who then gauge its meaning and relevance.

Who or what would you most like to collaborate with?

Alas, David Bowie.

What role does your genetic or cultural background play in your practice?

I am a child of Lithuanian American war refugees. My first language was Lithuanian, a beautiful, archaic, Indo-European tongue etymologically similar to Sanskrit. As the last “pagan” nation in Europe, pre-Christian deities, rituals, and traditions are an active part of the Lithuanian psyche, along with a special closeness to nature. This rich cultural heritage is scarred by a history of brutal occupation by powerful neighbors, strenuous resistance, mass murder and deportation, and the tragic complicity by a significant minority in the Holocaust. At age 66, I am still horrified by the worst and enchanted by the best in all that is Lithuanian. I have written extensively about all of this and am not finished.

What surprises you the most about what you are presently doing in your practice? If the 9-year-old version of you could witness your present self, what would they think?

“How could such a life be possible? And what am I doing with a dummy on my knee?”

What do you worry you will never be able to express?

The love that saves the world.

Can you recall your first memory of bliss in self-expression?

Playing Friar Laurence in a ninth-grade production of Romeo and Juliet

Who has been your greatest mentor, living or dead, real or imaginary?

Digby Wolfe, co-creator and first head writer of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. He was an incisive mentor, a spirit-boosting cheerleader, and a great and true friend. Just what I needed when we met in 1992. He is gone now.

What unchangeable fact has been most frustrating to you as an artist?

The inadequacy of words to convey deep meaning accurately.

If you have one goal for change in your artistic field, what would it be?

Greater opportunity for artists outside of the mainstream.

Have you ever had a physical illness, event, or impediment that has changed how you make art or approach art-making? And how?

At age 10, I came down with rheumatic fever and was bedridden for most of the school year. Kennedy had just been shot. The Cold War raged on. My parents worked, and I was alone mostly every day, either at home or in the hospital. I had bouts of great pain. Every time a jet from the nearby Air Force base flew over, I was sure World War III had begun. Every noise was proof of an intruder. I thought of suicide using my father’s pistol, hidden in the cupboard. At the same time, I had books—Poe, Greek mythology, and more—a world of fantasy and fear. I had the sensational music of The Beatles on my crystal radio. Toy soldiers fought epic battles on my bedsheets and blankets. Terror, pain, and escapist fantasy were most of my world. I went somewhere deep inside myself, where my inner world was more real than anything. That is where I think I acquired the imaginative, internalized mindset of an artist, although I didn’t know that. I thought I was just a weak, scared, sick kid, fattened by shots of cortisone.

Do you have a relationship with an animal in your life that influences your art process?

Bulve (Lithuanian for potato), my dachshund-terrier, keeps me simultaneously sane and crazy. My beehive is a source of daily fascination and was the subject of one of my performances, No Bees for Bridgeport.

If you could create a new public institution for your field, what would its mission be?

A museum of African American ventriloquists at legendary figure-maker Frank Marshall’s former home on the South Side of Chicago.

What is your relationship to criticism?

On a bad day, fear, and on a good day, indifference.

What is your relationship to praise?

Same as above.

Which would you prefer: to be a rogue artistic outsider or to fit within a community of similarly-minded creators?

Community is still best.

Are you more interested in the universal or the individual? How important is it to you whether you express yourself as a unique person, or rather add your voice to a collective conversation?

My work is individualistic and ego-ridden. I see this as a reflection of our time, where most of us are extremely self-centered.

If you could be anything besides an artist in human form, what would you like to be?

A human in artist form.

What would be the most thrilling moment or situation in time-space to find your art being enjoyed?

Those moments in performance when one feels mystically bound to the audience, both shaping and responding to a collectively-shared consciousness unfolding and changing in a flow of present moments.

Top photo: Kestutis Nakas performing in “Rustbelt Revival” at Links Hall in Chicago, August 14, 2009. Photo copyright John W. Sisson, Jr.