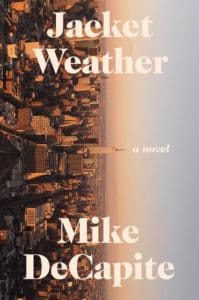

Jacket Weather Author Mike DeCapite Answers Some of Our #FiftyQuestions

On the occasion of the publication of his highly praised first novel, Jacket Weather, SSB is delighted to present Mike’s thoughts on his creative process in our signature #FiftyQuestions series. Mike will be reading excerpts from his novel at our partner Howl Happening on October 10th and then again with his friends Adele Bertei and Luc Sante on the 24th. Published by Soft Skull Press.

Jacket Weather is a tender love story that blossoms like a rose in the concrete of a city always on the verge. DeCapite’s effortless prose stirs echoes of certain New York School poets, of ‘cold rosy dawn,’ night streets illuminated by great bars and the music streaming out of them—the endless possibilities of a place where, despite persistent evidence to the contrary, ‘love is the heart of everything’. —Max Blagg, author of Slow Dazzle and Loud Money

Jacket Weather is a tender love story that blossoms like a rose in the concrete of a city always on the verge. DeCapite’s effortless prose stirs echoes of certain New York School poets, of ‘cold rosy dawn,’ night streets illuminated by great bars and the music streaming out of them—the endless possibilities of a place where, despite persistent evidence to the contrary, ‘love is the heart of everything’. —Max Blagg, author of Slow Dazzle and Loud Money

Jacket Weather is about awakening to love—dizzying, all-consuming, worldview-shaking love—when it’s least expected. It’s also about remaining alert to today’s pleasures—exploring the city, observing the seasons, listening to the guys at the gym—while time is slipping away. Told in fragments of narrative, reveries, recipes, bits of conversation and snatches of weather, the book collapses a decade in Mike and June’s life and shifts a reader to a glowing nostalgia for the present.

Poetic and compulsively readable, Jacket Weather invents a new genre—call it lyrical realism. Mike DeCapite casts a cool but affectionate eye on New York in the 2010s, as it lives on despite having become a replica of itself. Like Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex, Jacket Weather traces the lives of those who’ve stayed on after the party. It’s a love story improbably set at the beginning of late middle age, and it’s also a story of cities, survival, adaptation, desire, and a celebration of the small pleasures we invent and discover to offset unavoidable loss. —Chris Kraus, author of After Kathy Acker and Summer of Hate

#FIFTYQUESTIONS: MIKE DECAPITE

Describe your ideal workspace.

Here’s a romantic answer to a romantic question: a small upstairs room with a window, devoted to nothing else. I had a room on Hill Street in San Francisco with three windows, bare floor, a couple of bookshelves, and a gas heater. I could sit up in there all night in the dark and watch the whole theater of the sky, the clouds, the airplane lights, the lights on the hills, the fog sifting down into the backyards. But I got just as much done in a kitchen on Grand Street, in Williamsburg, or staring at a wall on Havemeyer. One of my favorite things I’ve written I wrote in a laundry room so wet that water collected in the divots of the typewriter keys. Jacket Weather I mostly wrote on the couch in our studio apartment on Seventh Avenue, with my partner, June, here the whole time. The ideal workspace is the one where you get the most done. I lived in a room on Folsom Street in San Francisco that just looked over an alley at the side of a house. Before I moved into it, I painted the walls and floor and stood some pine shelves around the walls for books and CDs. There was a desk and a Futon. I sort of turned myself around in that room, started over. That place still has a glow about it in my mind.

In thinking of the lulls and gaps or lost places in your practice over the years, who or what has re-energized you?

Usually when I hit on some new way that I can put things together. I need that and an idea of where to draw the frame.

What surprises you most about what you are doing right now in your practice? If the nine-year-old you could see you right now, what do you think s/he would think?

The nine-year-old me wouldn’t even recognize me because he’d be on a whole different wavelength, like a different animal. But my 29-year-old or 39-year-old self would be surprised that I’m writing without alcohol or cigarettes, and without missing them.

What do you worry you will never be able to express?

The way June looks to me while she’s asleep.

What unchangeable fact has been most frustrating to you as an artist?

My limitations are never far from my consciousness while I’m working, and my frustrations with them boil over now and then.

What do you feel are the greatest or most tenacious barriers to creating art over an entire lifetime?

Boredom, or laziness of imagination. Television. Alcohol, for me, anyway.

Do your dark nights of the soul tend to be constructive or destructive to your self-expression?

Really, I feel like I could answer that question honestly either way.

When does joy tend to visit you?

Usually when I’m alone, and with a change in the light, early in the morning or late in the day.

If you could amplify a specific sense, which would it be? If you could minimize a specific sense, which would you choose?

I’d amplify my sense of gratitude and minimize my sense of judgment.

How have your years in artmaking affected or influenced your sense of self?

I feel good when my work is going well and bad when it isn’t. If you mean long-term, that’s hard to answer because I don’t feel it’s separate from who I am. Looking back, I feel like I wasted a lot of time and should have gotten a lot more done. But I’ll look back and say the same thing about today if I remember today. The less I think about myself the better. But I’m okay with myself.

What do you suspect is your most powerful artistic blessing? Or blessing in general?

I have a capacity for elation.

Who or what do you feel is most invisible to others in your practice?

The amount of work and revision. Which is invisible even to me once I’m done.

How do you feel most often misunderstood or misperceived, either as an artist or in your work itself?

My work is true to the facts of my life, so it’s most often misperceived by people who know me, because they’re unable to see it as separate from me. Someone once said to me “What’s the big deal? You just wrote down what happened.” You would never say to a visual artist “What’s the big deal? You just painted what was there.” Factual or not, you’re inventing it for the page.

How important is it to you that others connect and understand and appreciate your work?

It’s the final step in the process. A reader completes the circuit. I hope I’m just setting up the conditions that allow something to happen in a reader’s head.

What is your relationship to criticism?

I take what I can use. Whatever rings true.

What is your relationship to praise?

Same as with criticism, I’m moved by what rings true. Unlike with criticism, I try not to let it affect my work.

What makes you most likely to shut down or go into dormancy as an artist?

Comparing my work with that of people whose work I love.

Do you have a particular skill or knack of which you are most secretly proud? Something you feel you can do that few others can, no matter how small?

Once I was hanging out in a studio while a friend was recording a song. Tony Maimone, who was producing the session, heard me fooling around with a toy glockenspiel I found on the shelf and set me up with it in the booth. It came out very well. But I’ve said what I have to say on the instrument.

Describe the greatest gift someone has given to you that invigorated your artistic expression?

The poet Amy Sparks started a magazine in Cleveland called angle and offered me a monthly column where I could write about whatever I wanted, and writing that column brought me back to life.

Are you more interested in the universal or the individual? How important is it to you whether you express yourself as a unique person, or rather add your voice to a collective conversation?

I always figure the individual is universal, that if something is true for me, it’s true for everyone. I’m often wrong about that, but it’s the assumption I proceed from in writing.

What would be the most thrilling moment or situation in timespace to find your art being enjoyed?

I’d like to get on the F train and see someone reading one of my books. Laughing. Not uproariously, you know. Not making a spectacle of herself. But enjoying it.